New Plymouth District councillor Dinnie Moeahu is whistling as our video call starts.

“When you’re as excited as I am about a meeting like this, I’m going to whistle!,” he laughs.

Whistling is not, however, something Puketapu hapū have historically done in relation to the New Plymouth airport. The land was originally confiscated by the Crown during the Māori Land Wars that began in Waitara in 1860 and it was taken again in the 1960s under the Public Works Act.

“It is a place of significance, and it has a sad past,” says Moeahu. “The land housed a lot of our cemeteries, our urupa, where many of our loved ones were buried. The contentious part of the history is that when they were developing the airport, they wiped out our urupa.”

When New Plymouth District Council decided to expand and upgrade the terminal in 2012, that sadness returned. The council started working with partners to commission designs and while Puketapu hapū was consulted as one of many special interest groups, Moeahu says it was “a tick box exercise”.

“We will go through the process we need to go through, meet the requirements we have to meet, but that was it. It was the bare minimum. It was ‘what can we get away with?’ There is a difference between consultation and engagement.”

Moeahu and other hapū representatives were determined to be at the centre of the decision-making process and make sure “their story was enshrined in this significant architectural landmark”. So, as Puketapu artist Rangi Kipa explained during a powerful korero called ‘Creativity as a Driver of Cultural Wellbeing’ at the Local Government New Zealand Conference, “we met with them and reminded them that we are the special interest group”.

“The land of the previous airport came from us. This is the piece of land that Puketapu takes its identity from. We reminded them that we’re tired of being invisible on our own landscape and that our tamariki and mokopuna deserve more.”

The council, acknowledging the mamae (hurt) associated with the site for hapū, and realising it had started the design process prematurely, went back to the drawing board and started over in a true partnership with Puketapu. The new process was one of co-design rather than consultation, involving continuous feedback loops between New Plymouth District Council, design firm Beca and Puketapu hapū representatives.

“It became quite evident that if the council wanted this project to work, they needed to listen to what the hapū had to say,” says Anaru Wilkie, a Trustee for the Puketapu hapū at the time of the project’s inception and Kaiāwhina at New Plymouth District Council. “They had a story about the site and wanted to have a footprint back on the site.”

When the council set up its company for the airport, there was a director seat for hapū and when the council controlled organisation was created for the new airport, Te Āti Awa iwi had a seat there and it was appointed by Puketapu hapū.

“That put us at the table,” says Wilkie. “Hapū were clear that they didn't want to have a transactional relationship with council in terms of just being there to monitor the new build and the old build going down. They wanted to be involved in the co-design.”

The groups developed a project charter that outlined how team members would work collaboratively during the design and construction process and it included principles around respectful relationships, communications expectations and transparency.

Wilkie explains: “The council went to the marae and listened to what hapū had to say in terms of the co-design. What their story is, what their history is with the place. Rangi facilitated and collated that information with Beca and the planning team.”

Through that process, the hapū’s view on the purpose of the airport became clear and the “minds started to meet”.

“An airport to the hapū is just like a whare – where you manaaki people, welcome people in and take care of them. That was really in their lane. They knew exactly what they wanted in terms of a whare manaaki.”

Moeahu, who in 2019 became just the second Māori to be elected to the council in the past 100 years, says part of the fight was convincing others involved in the project that “we are worthy of contributing. More importantly, what we had to offer was something that was missing from everybody else”. To him, the fact that many of the awards the project has received are due to the design, narrative and cultural aspects of the building proves that embracing Te Ao Māori in an authentic way is likely to lead to better, more unique spaces.

The four-year project was completed in 2016 and was a finalist in the Creative New Zealand Excellence Award for Cultural Wellbeing category at the 2021 Local Government New Zealand Excellence Awards. It also won a range of other design and architecture accolades. Judges from the Designers Institute of New Zealand Best Design Awards 2020 said: “Te Hono embraces tangata whenua expertise and narratives and weaves these throughout every aspect of the airport terminal, an impressive feat for an architectural job of this scale. The diverse range of artworks create a rich and engaging experience for all travellers.”

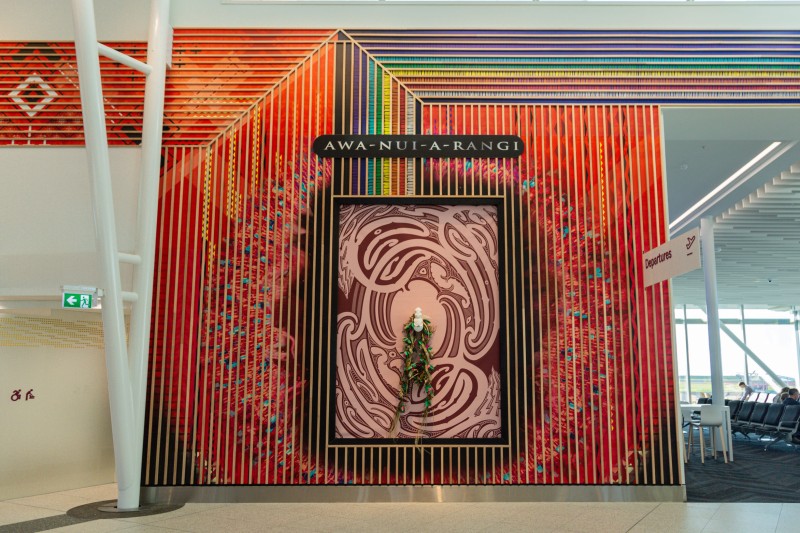

For Kipa, the origin story of Puketapu hapū is woven into the airport’s design. The narrative tells of Tamarau, who descended from the heavens after being captivated by the beauty of the earthly being of Rongo-ue-roa. Their union gave birth to a son named Awanui-a-rangi, the ancestor of Te Āti Awa. This story is represented in the two roof types of the airport intersecting – one representing Tamarau descending from the sky and the other, Rongo-ue-roa reaching from the earth.

The colours used are also narrative representations of the ancestral stories – green, purple and yellow – embedding further history into the heart of the project. There's something powerful about transforming the history of a place into a physical representation of its story, particularly a place that is often the first impression of the region. Airports are intrinsically emotive places, and the curved wall of the terminal seen on arrival represents a warm embrace of Taranaki welcoming you to its whenua.

Ngapuka plants, a native to the area, are planted in the outdoor space. Their vivid dark crimson flower is a connection to the plant’s presence on the old Puketapu Pa site, where they covered the hillside over 500 years ago.

The project also helped restore the Puketapu community by representing the narrative and language of the hapū, which now has a retail store in the terminal, ensuring their continued presence on site and an opportunity to generate income for their marae.

New Plymouth District Council stepped up to the inherent complexity and challenge of changing its original plans and direction. with mana whenua is a lesson that many organisations, Council and beyond, can learn from as a powerful and rewarding exercise.

“This was the first real co-design with iwi and hapū that we've embarked on,” says Wilkie. “We now understand what co-design, co-management is about. It enhanced the project, it created more value and it created a stronger awareness for those that are working on the projects, that there is value in incorporating the local history and tikanga within our Council projects. Iwi and hapū are good partners to work with. They add the uniqueness, the flavour, the sense of identity and a sense of place to council projects that you can't get anywhere else. It’s important to cost that engagement in. If you want it, you need to pay for it just as you'll pay for any other professional service.”

Moeahu says iwi and hapu had to fight “every step of the way” to have their voices heard at the time and it took challenging conversations and patience to build trust between individuals, but the end result has been profoundly rewarding and healing for all involved and it has definitely changed the way the council engages with iwi and hapū.

“Where we are now in 2023 is a very different space as a council to when I was elected in 2019, and completely different to ten years ago,” he says.

After Te Hono, Moeahu says a range of projects in the region - like the Coastal Walkway, the Waitara Marine Park, the Kawerau industrial development and the potential Tuparikino Active Community Hub – have all been inclusive processes and factored in engagement with hapū and iwi from the start.

“There are a lot of great projects happening in Taranaki and they are the examples we use when we know the council is doing it right.”

All of these projects – as well as greater iwi and hapū involvement in the council’s long-term planning processes – are the legacy of Te Hono, he says.

Moeahu says there is growing recognition “that [iwi] are not here to hinder progress. We want developments to happen”. They just need to happen in the right way.

“What the airport did is show that if you engage with hapū early, understand the dynamics and get them to add value to the project right from the beginning, the whole process flows beautifully and that’s one of the best things to come out of it.”

He believes this much deeper level of engagement from council has helped restore trust between tauiwi and mana whenua, and Kipa thinks it has helped tauiwi to be better citizens, too.

“If you haven’t as a council, embarked upon these courageous conversations about settling some scores that need to be settled, or at least challenge yourselves to meet conversations about what the future might look like, I really encourage you. Don't assume that silence means agreement. Actually, when the other party is not communicating back to you, there is a problem.”

For Kipa, creativity is a pathway for his people to stay human. Arts and culture can help restore visibility and “put back the things that were dismantled”. And Te Hono – from its fractious start to its inclusive end - is a powerful example of that.

This series, bringing to life the benefits of local arts and culture investment, was created in partnership with Creative New Zealand Toi Aotearoa.